Preventative Measures for C. difficile Infection (CDI

Dr. Chopra shares multipronged approach to reducing C. difficile infection (CDI) and the role of antimicrobial stewardship.

Episodes in this series

Paul Feuerstadt, MD: Teena, we know that C [Clostridioides] difficile is a major problem. We know that providers, patients, and health care systems are trying to cut down on the incidence of this. Can you walk us through certain techniques that can be done at an institutional level to decrease the incidence of C difficile and decrease the spread?

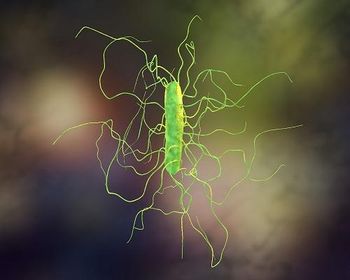

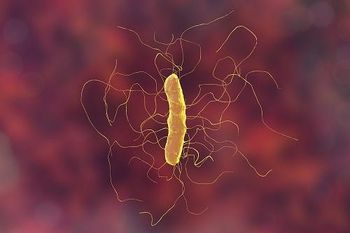

Teena Chopra, MD, MPH: Infection prevention is a huge challenge. As you mentioned, it’s a sporulating bacterium, and these spores can last on surfaces for a long period of time, especially if 1 high-touch surface is missed during environmental cleaning. It’s a multistep process that requires a multidisciplinary team, including nursing, infection control, pharmacy, environmental control, and your quality department. You want to have these patients in contact isolation rooms that are terminally cleaned with agents like bleach. You want to make sure you wash your hands with soap and water and wear appropriate PPE [personal protective equipment] before entering these rooms. If the patient continues to have diarrhea for a long period of time, every time the patient has diarrhea, the patient is spreading and shedding the spores, so the patient should remain in contact isolation for that duration of time. Those are some infection-prevention precautions you can take. Also, when we’re discharging patients, or transitions of care from 1 hospital to another, it’s very important to give those instructions to the family or the receiving facility because these patients can shed spores and transmit them to immunocompromised patients. These are some of the important nuances when you’re trying to help infection prevention with C difficile.

Paul Feuerstadt, MD: Excellent. Teena, can you walk us through a little on antimicrobial stewardship. Tom mentioned it earlier, but can you explain what that is, what it means, and why it’s important?

Teena Chopra, MD, MPH: Antibiotics are the single most common risk factor that cause dysbiosis in our gut. They change the microbiome of our gut, and it takes up to 3 months for the microbiome—for the dysbiosis—to restore in the absence of antibiotics. A single antibiotic given for a dental procedure is enough to cause dysbiosis and C difficile. Every time a patient comes to hospital for any other reason, we’re giving a lot of antibiotics to our patients. Stewardship is what we do, both in the community and in the hospital setting. That means you want to give the right antibiotic, at the right time, at the right dose; you don’t want to give unnecessary antibiotics. If you’ve started the patient on broad antimicrobials when the patient came in, you want to narrow it based on culture results, and you want to stop antibiotics as soon as possible because you don’t want to cause further dysbiosis, particularly in patients that are high risk for recurrent C difficile.

Paul Feuerstadt, MD: Yes, the dysbiosis is in effect, so the alteration to the microbiota or the weakening of colonization resistance leaves patients prone to this. We’re minimizing that significant impact on the microbiota.

Transcript edited for clarity

Newsletter

Stay ahead of emerging infectious disease threats with expert insights and breaking research. Subscribe now to get updates delivered straight to your inbox.